GEDI's Not-So-Final Frontier

The Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation instrument will cease data collection in January but not before fueling significant projects

Professor Ralph Dubayah of the Department of Geographical Sciences (GEOG) knew that if he could put a first-of-its-kind instrument into space to measure forests in 3D using a laser measurement method called Light Detection and Ranging (lidar), that project would advance important research.

He was right. Since the Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation (GEDI) instrument’s launch in December 2018, multiple researchers in GEOG have used its highly accurate forest height, structure, and surface elevation data in their own projects. These projects have focused on measuring and mitigating the impacts of climate change around the world, and in Maryland.

“You work so hard—so many late nights and so much stress to put an instrument into space and then create the data products—to see other scientists in your department able to utilize them to benefit their own research is fantastic. It makes it all worthwhile,” Dubayah said.

With GEDI now in its last year of data collection, we checked in with five GEDI mission team members to see how their research is addressing some of today’s greatest environmental challenges.

Changing the Way We Look at Land Use

Professor Matt Hansen, a GEDI mission co-investigator, and Research Professor Peter Potapov are interested in using GEDI data to get a better picture of how forests have changed over time.

In late 2020, a $12.75 million grant paid for by the Bezos Earth Fund fueled that interest further. The grant, which seeks to create satellite systems to track Earth’s changing physical landscape and related economic activity and land use from 2000 onward, was specifically awarded to changing the way we look at land use Hansen and Potapov’s Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) Lab via the World Resources Institute (WRI).

Hansen said this first-of-its kind system will address a major problem in current land-use change mapping: disjointed data that leads to unclear results. “Everybody calls forests something different, and everybody maps and estimates cropland differently. When you synthesize the data, from a bottom-up perspective, you get very inconsistent and poor information,” Hansen said.

Through the “Land & Carbon Lab” project with WRI, the GLAD Lab’s research faculty, postdocs, analysts, graduate students and student interns aim to solve that issue by late 2025. They’re downloading GEDI data and other satellite information, then are reviewing, correcting and identifying signals for certain land covers and uses.

The team is then applying algorithms that allow them to more automatically and accurately map these changes over time.

“We developed a tool to extrapolate the GEDI-based forest structure measurements using the global USGS/NASA Landsat data archive and machine learning, and the resulting global forest extent and height maps show the change of forest area and structure from 2000 to 2020,” Potapov said. “So far, we’ve found that the forest area decreased by 2.4 percent, and that the largest reduction of tall forests was in tropical Asia and South America, followed by Africa, corresponding to the expansion of agriculture and agroforestry.”

“When you do global monitoring like this, you get an internally consistent story,” Hansen said. “You can compare apples to apples in order to see who is deforesting the most, who is making the most improvement and reducing deforestation, or who is converting the most wetlands.”

More information on the economic changes related to the land-use changes identified by the GLAD Lab will be provided by WRI. WRI is also tasked with providing information on associated carbon emissions.

Setting Some Rules to Get Good Results

Since serving as GEDI mission research scientists, Assistant Professor Laura Duncanson and Associate Research Professor John Armston have ensured that the data provided by GEDI doesn’t further complicate the climate change conversation.

Just before GEDI’s launch, Duncanson and Armston created a “biomass protocol” document that provides researchers from around the world with a list of best practices for using GEDI and similar instrument data to create biomass estimates. Biomass is the living material—a.k.a. carbon—that lives within vegetation. The more carbon that is stored in forests, the better, as the carbon released from deforestation is a significant climate change contributor.

Duncanson and Armston hypothesized that if GEDI was providing new data, without new guidelines for its use, there would be too many international researchers creating too many biomass products—and no easy way for decision-makers to know which estimates are most accurate. “We realized pretty quickly that researchers were just going to confuse everybody by using GEDI and other satellite data to put out many different products that all have a little bit of a different flavor, a little bit of a different approach to answering the question, and that all quantify uncertainties differently,” Duncanson said. “We wanted to have everyone follow the same methods for validating them so at least that would be consistent.”

Their “Aboveground Woody Biomass Product Validation Good Practices Protocol” was published in March 2021. A few months later, the protocol inspired the Biomass Earthdata Dashboard: a user-friendly web platform through which discrepancies are resolved, and harmonized estimates of biomass created. At last fall’s 26th annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), Duncanson debuted the site to the highly exclusive list of attending global leaders, showing them the latest mismatched maps and explaining their hope of creating a site where visitors, especially policymakers, can easily extract information and make informed decisions.

Since then, Armston and Duncanson have developed algorithms that convert GEDI data into biomass estimates. In late 2021, they created one—as explained in a Remote Sensing of Environment journal article earlier this spring—capable of measuring how much aboveground carbon is found in the world’s forests.

“GEDI doesn’t measure biomass, it measures vegetation height and cover,” Armston said. “That paper describes how we convert those estimates to biomass using relationships between structure and mass, and how we model that relationship over the whole globe.”

Mapping Forests on the Ground ... and in Maryland

Professor George Hurtt and Research Professor Michelle Hofton, GEDI co-investigators, are taking on GEDI-fueled projects that hit a little closer to home.

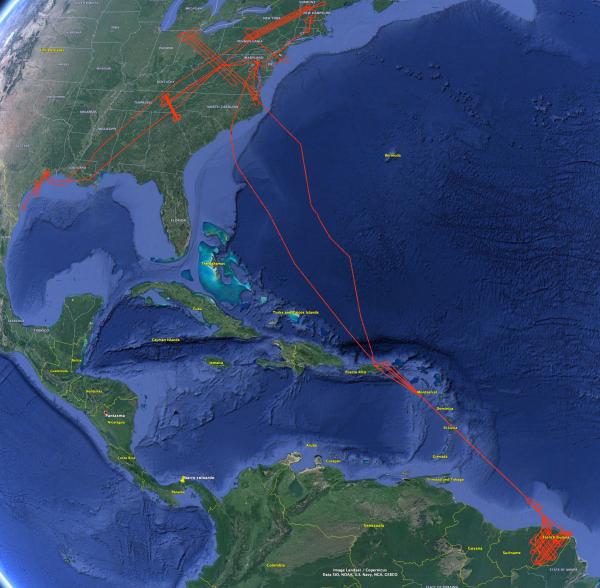

Hofton is collecting lidar measurements from airplanes through the Land, Vegetation, and Ice Sensor (LVIS), a 3D data collection method that preceded GEDI and, Hofton explained, “built the data community and got people familiar with what data products GEDI would put out.”

“LVIS is an airborne facility run by NASA that collects lidar data just like GEDI,” Hofton said. “What we’ve done with LVIS in recent years is fly on GEDI tracks and collect calibration and validation data for GEDI, so that when we intercompare the two, we can use it to improve the GEDI data precision and accuracy for people to use in biomass estimation.”

Since 2019, LVIS has underflown GEDI tracks in North Carolina’s Coweeta Experimental Forest, Costa Rica’s La Selva Biological Station, West Africa’s French Guinea, and other parts of the Eastern United States. In late 2022, Hofton plans to fly over Papua New Guinea and Indonesia for another GEDI calibration-validation project.

Hurtt is no stranger to LVIS, or to aircraft lidar data. Before GEDI, Hurtt and Dubayah used high resolution aircraft lidar data to map how much forest carbon was stored in Anne Arundel County and Howard County in Maryland.

From there came additional projects to map forest carbon across the state of Maryland; then Maryland, Pennsylvania and Delaware; then the 11-state region spanning Virginia to Maine; and now the nation and globe using GEDI.

“But we aren’t just mapping forest carbon now,” Hurtt said. “We are using that information in computer models to explain past changes, and to quantify how much carbon our forests can absorb in the future.”

At COP26, Maryland Department of the Environment Secretary Ben Grumbles announced the state would be using these new data as an official forest carbon data source. Undergraduate students have been granted funds to implement this same system on campus, too, through the Campus Forest Carbon Project Hurtt has also helped create. “It’s a microcosm of what we are trying to do for the state of Maryland, which in turn is a microcosm of what we are trying to do for the country, and world using GEDI,” Hurtt said.

Published on Mon, Apr 4, 2022 - 3:00PM