New Anthropology Lab to Extract, Study Ancient DNA

What was once a single, roughly 250-square-foot office in the basement of Woods Hall is now a two-room lab through which University of Maryland graduate students—and some properly trained undergraduates—can try their hand at extracting and studying DNA from ancient bones.

The Archaeogenetics Lab is the second DNA lab launched and led by Department of Anthropology Assistant Professor Miguel Vilar in the last year. The first, the Evolutionary Anthropology and Genetics Lab (EAGL), opened its doors during the spring 2025 semester, and uses “modern DNA” from the present moment to learn more about the past. In EAGL, 8-10 students at a time have the opportunity to spit into a test tube and learn more about their ancestral origins, whereas in the new Archaeogenetics Lab, just 1-2 students are able to conduct experiments that move in the opposite direction—using DNA from years past to validate or refute what hypotheses have been developed based on other clues, like the geographic location of certain bones and items found alongside them.

“When you spit into a tube and find out about who your ancestors were, scientists are kind of inferring based on your modern composition what your grandparents or great great great grandparents were like. Now with ancient DNA, we can actually see what they are like—we don’t have to guess,” said Vilar, who is known internationally for his genetic anthropology work. “With ancient DNA, we can also see change over time. We can get DNA from something that lived a century or a millennia ago, and actually see evolution happening, and that has got people really excited.”

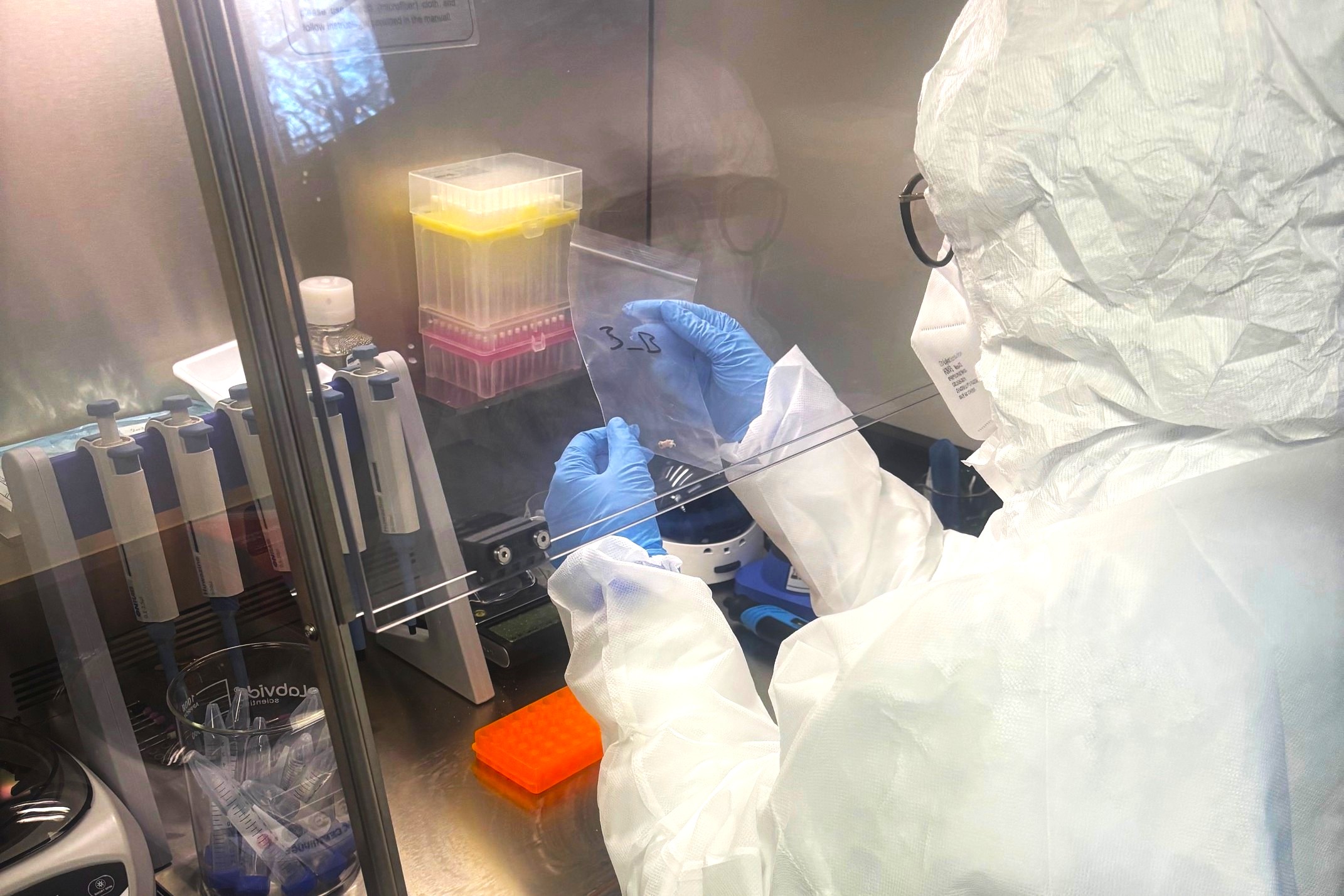

As eager and excited as students may be to participate in Vilar’s newest lab, its maximum occupancy is limited due to the special precautions that must be taken in order to not contaminate the ancient DNA. The lab has two rooms so that students can get rid of their street clothes and don the appropriate protective gear, including a full-body suit, two pairs of gloves, and a mask. The room where DNA from ancient bones will be extracted is sterilized with UV lights and filtered with High Efficiency Particle Arresting (HEPA) filters so that there is virtually no modern DNA present in that space.

“Inside of bones and teeth are where the main sources of ancient DNA are, so you have to clean the bones very thoroughly, drill into them, and extract the DNA from the inside. When you do that, the DNA is already degraded, so you have to be wary that anything in your body could contaminate that,” explained Vilar.

The ancient bones that Vilar and graduate students have begun working with are roughly 1,100-year-old bones from fish and domestic animals from Iceland. The bones are from a collection that ANTH Associate Professor George Hambrecht has assembled over the years for his research on the relationship between humans and animals, both wild and domestic, in Iceland, since its first colonization by humans in the later 9th century CE.

“The study of ancient DNA has revolutionized the study of zooarchaeology, which is the study of animal bones produced by archaeological sites. Ancient DNA analysis can help us understand the origins of domestic animals, and in the Icelandic context, where we have well-defined and isolated populations, it can help us understand how animals and fish adapted to their environments as well as to human management,” Hambrecht said.

Vilar hopes that one day he and students may be able to extract ancient DNA from human remains too, experiments which could help answer a large number of medical and other questions about humanity.

“We now live in an environment where there are new diseases, like Covid, that weren’t around in the past. So, what was our genome like a thousand years ago, and how has it changed so that we are now susceptible to some diseases that we weren’t in the past?” he asks. “There are uses for ancient DNA in medicine, in the study of evolution, in academics, in our understanding of diversity, and so much more.”

Published on Fri, Dec 5, 2025 - 2:02PM