Study: Can AI Reliably Accelerate Research?

GVPT researchers compare GPT to other machine-learning models, plus trained human coders

Though many Americans may have only recently heard about artificial intelligence due to the exploding popularity of ChatGPT, behavioral and social scientists have been using machine-learning systems to explore complex problems and dynamics for years.

Johanna Birnir, a professor in the University of Maryland Department of Government and Politics (GVPT), and her students have spent the last half-decade testing whether machine-learning models can be used to more quickly and accurately “code” decades of data on protests by various ethnic groups. Coding—a way of identifying information by assigning a number to it, like “0” if an article does not discuss what you’re searching for, and “1” if it does—has traditionally been done by humans, making the process not only time-consuming, but also cost prohibitive because of how many individuals need to be hired to help.

Now, Birnir finally has some answers to the questions she’s been wrestling with; answers that are captured in a new, PNAS Nexus paper she co-authored with three current GVPT doctoral candidates, a 2023 GVPT Ph.D. alumnus, and a University of Texas at Austin colleague and her Ph.D. students.

One of the takeaways from their study is that some machine-learning models are better than others. Using data on ethnic groups from the All Minorities at Risk (AMAR) dataset, the researchers compared GPT with two earlier machine-learning models, Newsmap and BERT, to see which had the best overall performance in coding 2021 news articles and websites for protests by AMAR ethnic groups.

BERT scored 0.020 points higher than GPT in its ability to identify only relevant data (precision), but GPT performed 0.149 points better than BERT in its ability to find relevant cases (recall).

“This is a fast-moving field and so I’m not surprised that GPT did so well. In fact, as we were writing this, multiple new versions of GPT were released, and we would retest on each iteration, if possible,” said the paper’s lead author, Henry Overos, GVPT Ph.D. ’23, an assistant research scientist at UMD’s Applied Research Laboratory for Intelligence and Security. “Each new version tends to outperform the previous one. But the fact that BERT still performed almost as well as GPT shows that there’s still room to grow, and that even relatively older models are still powerful tools for a variety of research tasks.”

Another takeaway is that, contrary to current research belief, it may not be wise to solely rely on humans for projects like these, either—even if they undergo intensive training beforehand.

“Human coding is considered the ‘gold standard’,” said Birnir. “But what we found was that when the students at UT Austin, who were specifically trained for this study, were coding cases that they were familiar with—in this instance, U.S. protests—they did better than the machines in terms of coding consistency between students. That wasn’t necessarily the case for their coding of cases from contexts that they’re unfamiliar with, so, we found that in spite of their training there was this unequal accuracy in coding by students that depended on their prior knowledge.”

Given these results, the authors suggest that AI models like GPT be utilized by researchers in conjunction with human coders to increase confidence in findings when the models mirror human results, and to give researchers pause when they differ.

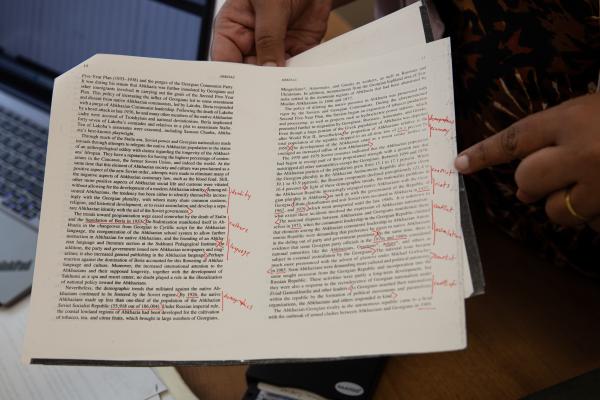

For a follow-up study Birnir is leading, two other GVPT doctoral candidates, Juan Diego Alvarado and Ojashwi Pathak—another author of the PNAS Nexus paper— are currently reviewing and, if needed, digitizing early AMAR data. Much of that data is stowed away in filing cabinets and saved to floppy disks at UMD.

Birnir’s next study will fine-tune the GPT models to code for ethnic group grievances, state repression, and fine-grained levels of protest, from peaceful to violent.

Though she acknowledges that the science isn’t quite there yet, Birnir believes that using AI in this way has the potential to powerfully assist social change.

“Academic researchers are always five years behind the activist community and policymakers because we’re carefully collecting data, curating it and only then making it available. And by the time we do make it available, it's less useful to the community because they've moved on,” she explained. “But if you set these models up in such a way that you can be distributing accurate data almost as soon as you're coding it, then you can start analyzing events as they are happening and disseminate important information to people all over the world more quickly.”

Read “Coding with the machines: Machine-assisted coding of rare event data”

The photos of Juan Diego Alvarado and Ojashwi Pathak coding MAR data for Birnir's follow-up study are by Rachael Grahame

Published on Thu, May 9, 2024 - 10:30AM