UMD Graduate Students Create AI-Powered Tool to Extract Threatening Language

A paper recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) explains the science behind a new, online tool that can help users determine what share of a speech, article or other text uses threatening language.

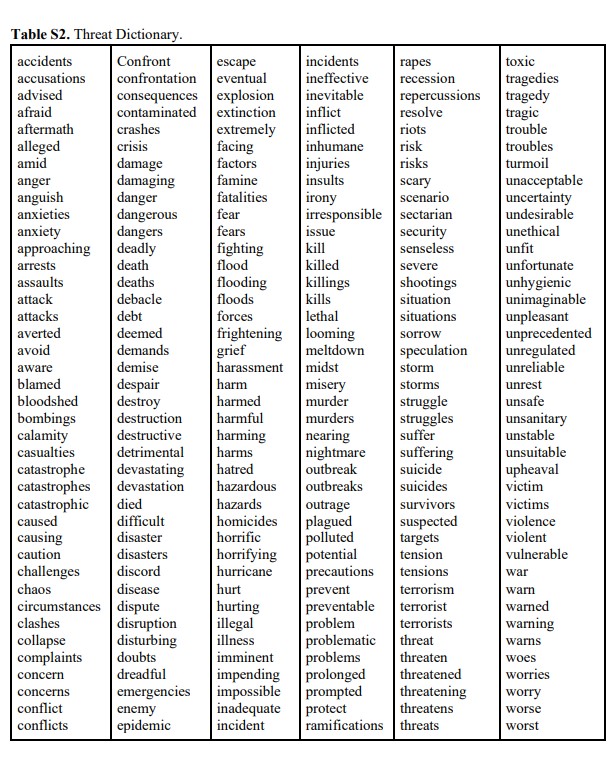

Led by Virginia Choi, a Ph.D. student in the University of Maryland’s Department of Psychology (PYSC), the paper outlines how she, fellow PSYC Ph.D. student Xinyue Pan, former PSYC professor Michele Gelfand, and Snehesh Shrestha, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Computer Science, created a 240-word “threat dictionary” through a relatively new process: Feeding Wikipedia articles, Twitter posts and randomized web pages through an AI-powered word-embedding model that draws comparisons between words with the same meaning. The team chose those platforms to ensure that they could capture what threatening words are used in both formal and informal contexts.

“In the past, people would use subject-matter experts to come up with a list of words that really capture the psychological construct of interest; they would bring a bunch of people together who know a lot about it, go through the literature on it, and go from there. That’s a closed room process that might not really reflect how people talk about something,” explained Choi. “Using word-embedding models, overall, you are sampling more of the way people are talking about things, correctly.”

To ensure the words they came up with could truly communicate varying levels of threat depending on the words used as well as their frequency, the team uploaded historical documents to an analytical tool—now available for public use here—to see whether an increased prevalence of threatening language matched with particularly troublesome times in U.S. history.

“It took a lot of work to iterate, apply, and test the dictionary to ensure validity,” said Shrestha, who took lead on building the online tool and sourced, gathered, and helped analyze data from newspapers and presidential speeches. “It is one of the first of its kind to provide an index measure of threat.”

The tool’s ability to provide insight into how threatened people were feeling during certain points in history—including history in the making, where COVID-19 is concerned—is among the researchers’ top takeaways.

“With a supervised machine learning classification test, we showed that threat dictionary was one of the most important features in classifying whether a tweet explicitly talked about COVID-19,” mentioned Pan, who was in charge of collecting and analyzing the 240,000 Twitter posts the team studied. “We also showed that among COVID-related tweets, the use of threat words increased as the pandemic escalated and tweets with more threat words were more likely to be retweeted.”

Having completed her thesis through this project, Choi is now studying for her comprehensive examinations and figuring out how she might use this tool in the future.

“In the future, as more things come online and accessible, I think it would be really cool to immediately look at what was going on during the cold war, what was going on in the gilded age … we could use these new tools to reassess history,” she explained. “But, after experiencing how easy it is to look at texts this way, I'm interested in using linguistic analysis to figure out the pulse of the workplace.”

The threat dictionary and others liked it being applied in one such way is the team’s ultimate hope.

“It has been a sheer delight to work with Virginia and the team on this project; it was a truly interdisciplinary effort,” said Michele Gelfand, who now acts as a Professor of Organizational Behavior and Psychology at Stanford Graduate School of Business. “We hope the threat dictionary will be of broad appeal to people across the social and computational sciences to be able to understand the contagion of threat across social media and its collective consequences.”

For the full research paper, click here. To access the tool, click here.

Disclaimer: The threat dictionary is a relative measure, not an absolute measure, and should be used with caution for academic research purposes only.

Published on Thu, Feb 10, 2022 - 11:15AM